Published: 02/07/2024

Interview by Jamie Hansen, Global Health Communications Manager

Medical professionals and scientific researchers are some of the most trusted sources of information — a status that can be harnessed to effectively communicate vital public health information.

But the public’s trust in such expertise can also be used toward opposite ends. A new study led by Stanford graduate student Mallory Harris finds that individuals who appear to be biomedical experts may also be important anti-vaccine influencers on social media.

Harris, a biology PhD student and infectious disease modeler in the lab of Erin Mordecai, associate professor of Biology in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, joined with colleagues at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public to investigate the scope and importance of perceived experts acting as potential anti-vaccine influencers. Mordecai, PhD, is a coauthor.

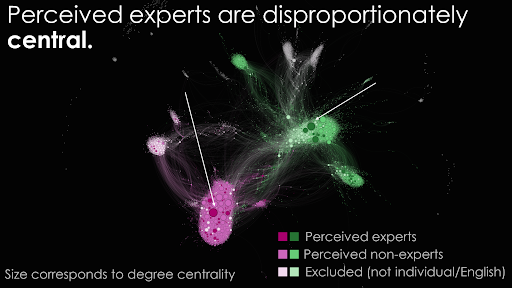

The researchers identified a network of nearly 8,000 interconnected users from a database of 4.2 million tweets about COVID-19 vaccines from April 2021 — a critical window for early vaccine uptake.

They found that perceived experts in the anti-vaccine community were more likely to receive likes and retweets compared to non-experts. They also found that these perceived experts in both pro- and anti-vaccine communities often shared scientific articles. However, in the anti-vaccine network, perceived experts, like non-experts, regularly shared low-quality sources likely to contain misinformation.

“Perceived experts are a key group of anti-vaccine influencers, and any efforts to counter vaccine hesitancy must take that into account,” Harris said.

At a time of waning public trust and rampant misinformation, what do these findings mean for public health communication? We sat down with Harris to find out.

What sparked your curiosity about this health communication question as a disease modeler and biologist?

As the pandemic began, I was working on disease modeling projects that were trying to communicate about how the pandemic might unfold and the measures that we could take to prevent the worst consequences. I started to realize that people weren’t just listening to the information provided by scientists and infectious disease modelers — other influential voices were spreading misinformation, often using credentials that implied expertise they didn’t have. On top of that, a small minority of actual experts making fringe claims about the pandemic received disproportionate attention.

I began thinking about what researchers could do to reach more people and address misconceptions about infectious disease research directly. When I looked at the research on this topic, I saw a big gap. People have noticed this phenomenon of perceived experts spreading misinformation for a long time — but this effect hasn’t been quantified and described systematically. I decided I could use my background in thinking about networks and analyzing large data sets to see if we could provide data to address how big and important this group of perceived experts in the anti-vaccine community actually is.

Given the amount of social media content generated about vaccines during the pandemic, how did you choose what to focus on?

April 2021 was this really important moment for vaccination in the U.S., because that’s when eligibility started to expand to all adults. We had studies showing the vaccines were broadly safe and effective, and a lot of active scientific discussions were happening about emerging data.

We focused on Twitter because it was one of the top places people went to hear from experts and journalists. Twitter also provides pretty limited information about the users in its feed, so I hypothesized that it would be useful as a first place to test these ideas about people making quick judgments about the qualifications of their sources.

Importantly, we went to great lengths to anonymize the people included in the study. We did this to protect privacy and to keep the focus of the study off of any given individual. We wanted to think more about this system and how it was operating. We classified people as experts based on the educational or professional credentials they provided in their profile. Our study didn’t verify these credentials, focusing instead on how their expertise might be assessed by an online audience. In total, about 13 percent of users in the study were perceived experts.

What did you learn about how perceived expertise impacts an individual’s social media influence?

Perceived experts in both pro- and anti-vaccine communities received a boost in terms of the amount of engagement they received — and the size of the boost is essentially the same. We also found evidence that perceived experts are more influential than other individuals in the anti-vaccine community: They more often held central network positions where they could reach more people, and were nearly 1.5 times more likely to receive retweets on their median posts. So while some people might assume that the anti-vaccine community doesn’t care about experts, we actually see that they have a similarly heightened attention to their own set of experts. However, these experts may not be sharing accurate information. We found that they were as likely to share low-quality sources (sources that regularly fail fact checks) as other users in the anti-vaccine community, whereas perceived experts in the pro-vaccine community virtually never did.

What findings surprised you most?

We saw perceived experts in both the pro-vaccine and the anti-vaccine community sharing many more scientific articles than non-experts. So these perceived experts in the anti-vaccine community did not just have credentials in their names — they were behaving in many of the same ways as their counterparts in the pro-vaccine community, such as discussing scientific papers.

We also looked at people who were bridging the anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine community — those who had people from both communities are engaging with them. Perceived experts were massively over-represented as bridges between these communities. We saw that the things they posted were often super in-depth commentary on scientific papers and pre-prints.

Often, when we’re learning about how to communicate our science, we’re told not to make it too technical — that people don’t want to hear all the details. But what we actually found was there was a big appetite for that, regardless of vaccine stance.

Mallory Harris, Stanford PHD Student in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences

Often, when we’re learning about how to communicate our science, we’re told not to make it too technical — that people don’t want to hear all the details. But what we actually found was there was a big appetite for that, regardless of vaccine stance.

What are the implications for medical professionals and how they communicate about public health issues such as vaccination?

Our study covered the period when the Johnson & Johnson vaccine was paused due to reports of rare blood clotting events. We saw experts in the pro-vaccine community sharing the data as they emerged and discussing what they might imply.

For physicians, addressing concerns openly and quickly, while also being careful not to overstate the risks, can be valuable. Prior surveys suggest that vaccines aren’t enough of a focus in medical education, and that it’s important to equip medical professionals to really understand the best available data and be prepared for these conversations with patients, which can be really difficult ones to have.

Experts can also work more effectively as a group to convey scientific consensus around challenging or contested topics. We’ve seen this approach in climate communications — a moving away from contrasting experts on both sides of an issue, to instead highlighting the preponderance of evidence. This can give an audience a better sense of what the expert community actually believes.

Finally, this paper comes amid discussions about what the standard should be for medical professionals. It is worth considering what might constitute a violation of a doctor’s professional responsibilities — for instance, sharing information that is extremely out of line with the scientific consensus and the body of evidence in a manner that might endanger their patients.

What are the biggest takeaways for those trying to access credible public health information online?

It could backfire to simply tell people to look for experts and trust what they are saying.

We have to go a level deeper and question who these people we’re listening to are. What exactly are they an expert in? Have they published on this subject? Might they have financial or political conflicts of interest? We can also try to understand an individual’s reputation in their scientific community.

It could backfire to simply tell people to look for experts and trust what they are saying. We have to go a level deeper and question who these people we’re listening to are.

Mallory Harris, PhD Student in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences

Social media platforms can also take more action to ensure that people are receiving reliable information on these websites, whether that’s through moderating content, changing the algorithms that determine which posts show up in our feeds, or redesigning how the platforms look. We found that signals of expertise carry a lot of weight, so platforms might consider additional ways of verifying those credentials and indicating whether a user is indeed an expert on a particular topic.

These steps, taken together, can help ensure we’re not just listening to experts, but trustworthy ones.

Acknowledgments

Harris conducted this research as a graduate student at Stanford and visiting student researcher at the Center for an Informed Public (CIP) at the University of Washington. Jevin D. West, from the CIP, was senior author. Ryan Murtfeldt and Shufan Wang from the Information school at the University of Washington were co-authors. Mordecai is a Faculty Fellow in the Woods Institute for the Environment, the Center for Innovation in Global Health, the King Center on Global Development, and a member of Bio-X.

Cover photo credit: COVID-19 vaccine vials, by Daniel Schludi, unsplash.com